Being neat and tidy has never been the hallmark of my mostly uneventful life except for a few incidental aberrations here and there. Since my brother Sheelabhadra is gone from this world now, I can say without fear of a mild rebuke or a reprimand in the form of a simple word or two that my exemplary ‘Guru’ in those regards was no other than my brother himself. No, no, no.... He didn’t teach me to be laggardly or untidy or mischievous or any of all those uncomplimentary things though he spent hours at a time driving into my not-so-fertile and stubborn brain the simple logic and beauty behind both mathematics and language. Oh, I loved his teaching style and his read on me. He knew me better than myself.

Being neat and tidy has never been the hallmark of my mostly uneventful life except for a few incidental aberrations here and there. Since my brother Sheelabhadra is gone from this world now, I can say without fear of a mild rebuke or a reprimand in the form of a simple word or two that my exemplary ‘Guru’ in those regards was no other than my brother himself. No, no, no.... He didn’t teach me to be laggardly or untidy or mischievous or any of all those uncomplimentary things though he spent hours at a time driving into my not-so-fertile and stubborn brain the simple logic and beauty behind both mathematics and language. Oh, I loved his teaching style and his read on me. He knew me better than myself.

On the other hand, my illustrious brother taught me to be hard-working like the German students who, he said, worked eighteen hours a day or more. He also gave me a book titled ‘Call It Experience’ by the American writer Erskine Caldwell to read. I read that book many times, and told myself ‘What is new in chopping wood? I have been chopping wood with my brother Nantu ever since I could lift a ‘kuthar’ over my head’.

Later in my life, I worked eighteen hours or more at a stretch - that is a bit of a stretch, I solemnly admit - when a computer program in my graduate studies or a report on what I was working was due. Otherwise, I took my own sweet time pondering over various facets of the problems associated with my studies or the project I was handling…

While my brother tried his level best to make me tolerably educated and self-supporting, I soaked in the soothing ambience of seeing numerous books that lay on his small bed in various states of being open, semi-open and ready to be opened. ‘Why close a book now only to reopen it again sometime later?’ was the message that went out clear and loud from the pile of books on his bed.

Prior to my brother’s book-laden room being thrown into that disorganized state, I saw his notes taken during the post-graduate lectures in Calcutta University carefully strewn around in his room until one-night Dr. Siben Barua came to our house and took away the note books with yellow covers away for his personal good use. I felt that I had lost something very important. I consoled myself that the note books were being put to good use by a man our family admired. Siben Barua was so respected in our family that how we did a thing was compared to what Shibu of my admiring mother would’ve done. That was a tough comparison to beat. Nobody in our house came out to be winner.

There were many suits - summer as well as winter - that hung from a wooden ‘alna’ in my brother’s carefully disorganized room. The suits belonged to my ‘pehi’s son who was an officer in the British Indian Air Force, and my brother-in-law Niru Vinihi, always on the lookout to make life easier for all of us, borrowed the suits for Sheelabhadra to wear to his university classes. There were many English teachers. I scratch my head now for their names. Sheelabhadra didn’t like the idea of suiting up in borrowed suits. He abhorred doing anything at other’s cost. He used to say a Bengali saying, ‘tale nengti, opare jama’

Once when my sisters, on instructions from my mother and taking advantage of my brother’s absence, tidied up his bed and other things on the floor in the his single-room cozy house, things didn’t go well for our sisters for the rest of the day till my mother stood at the corridor separating his room from the main house and called him to eat sliced mangoes. He couldn’t resist that call. He liked fruits. He came out of his room and devoured sliced mangoes as fast as the mangoes could be peeled and sliced. He avoided the seeds, though. They were for me.

In the later years of life when Sheelabhadra couldn’t come home on this or that account, my loving mother always sent baskets of the choicest mangoes to Guwahati for the consumption of his family. Out of one of those mango seeds thrown around in the premises of his residential quarters at AEC, grew a short mango tree that gave bountiful mangoes. I told that story to a gentleman at about the same time Sheelabhadra was retiring. ‘What would Sheelabhadra do with the mango tree?’, asked the man. ‘He would get his sons to chop down the tree. What else to do?’, came my mischievous reply. Of course, the man didn’t get my point.

When Sheelabhadra came home from Calcutta on any vacation, he regularly took up small municipal or other contracts to build bamboo culverts or dig water wells in the surrounding village areas. On those occasions, my only ‘pehi’ used to invite us, the brothers, to eat ‘dupariar ahar’ at her house. She lived nearby. The ‘pehi’s family was from Barnagar. The family with many other families fled upper Assam to Barnagar during ‘manor akroman’

The loving ‘pehi’ used to cook up a veritable storm with the choicest preparations. She herself served us pushing this item or that item. We two - me and my older brother Nantu – who never shied away from our regular eating – would eat a prodigious amount of good food in the celebrating stance of ‘the more, the merrier’. While Sheelabhadra, finishing his own moderate eating, would sit there on a high four-legged ‘pira’ awaiting our disengagement from our stupendous eating session, we would keep on eating till we couldn’t eat no more. What a relief it was for us as well as Sheelabhadra but for entirely different reasons!

‘Pehi’, who lost her young brother in the death of our father, couldn’t deny us more food. So, she would keep on piling on our metal ‘kahi’s. On one occasion, we came home only to hear Sheelabhadra tell my mother, ‘These two have become absolutely uncivilized. They kept on eating long after I was done’. That was the sternest rebuke I ever received from Sheelabhadra. A correction - three years ago when I wrote an article for a newspaper, he asked me, ‘What’s your concluding point? It’s not clear, or did you have a point?’ Well, that was the occasion, I now believe, Sheelabhadra embraced the whole-hearted responsibility for the upkeep of our family in his own hands.

Nantu received some hard slaps on his face from Sheelabhadra when he pilfered and sold a few gold coins from my mother’s trunk to support his ‘beedee’ and frequenting tea-stall habits. My mother saved those coins for the worst economic times, and now they were gone. Reflecting back on those times, I think my mother ignored those times when they came or she pretended that they weren’t there yet. She did that with our two houses at Dhubri, houses eventually usurped by renters.

If you think that Sheelabhadra had no sense of humor or a liking for artistic things, think again. First of all, he was a good singer. He not only hummed songs, he sang full-throated Bengali songs in the house without caring what others thought about his singing. The thing I remember is that there was a singer with the last name ‘Mollick’. He liked Sachin Dev Barman, Saigal... He sang often the song, ‘Din guli more sonar khachaey roilana, railana.........’. When one morning two years ago, I heard a favorite song of Sheelabhadra being sung on a TV program, I called his house and told her daughter-in-law about the program. She told me that was what ‘Baba’ was listening to.

Sheelabhadra didn’t spend his time in Calcutta with his nose buried in books. He went to theaters, movies and soccer games. He saw many Charlie Chaplin movies in Calcutta. He used to discuss those movies with close friend Animesh Chakravorty of ‘Khudimari’ in the suburbs of Gauripur. Animeshda who had earned in MA in English worked in the life insurance industry.

Sheelabhadra spoke very highly of the talents of the famous magician P. C. Sorkar. Once, he told us with suspense, trill and humor, that he was waiting like others in a large hall for Sorcar to show up to start the program. But, there was no show of the famed magician for more than an hour. The audience became impatient and some started to leave the hall. Just then appeared Sorcar on the stage. When someone in the audience asked Sorcar about his late appearance, Sorcar silenced him by asking him to look at his watch and others’ as well. It was, lo and behold, the right time for the show. It was mass hypnosis. I had seen an act like that in an international conference in Atlanta.

Once after a magic show, Sheelabhadra and Jean, the oldest son of Promothesh Barua, boarded a bus to come to Ballygunge residence of the Barua family. But, when the bus stopped, Jean was nowhere in the bus. Jean, the conductor told Sheelabhadra, got off the bus when the conductor shouted ‘Ballygunge, Ballygunge’ to attract passengers bound for Ballygunge. Absent-minded Jean was studying philosophy in Calcutta University. 14 Ballygunge Road was a off-quoted landmark in Calcutta as well as Gauripur. .

Sheelabhadra didn’t like to consciously cause any harm to animals, insects etc. One day I was with my friends playing soccer. I came home and saw him and Nantu on each side of the living room silently watching a ‘mokora’ carrying a huge round pouch of eggs in its underbelly slowly making its way to the other side of the room. ‘Why wait to destroy the insignificant ‘mokora’? Time is now!’, I must have thought in a flash. I stomped the ‘mokora’ dead. The agony and pain in my brother’s face was devastatingly clear. I learned my lesson for life...

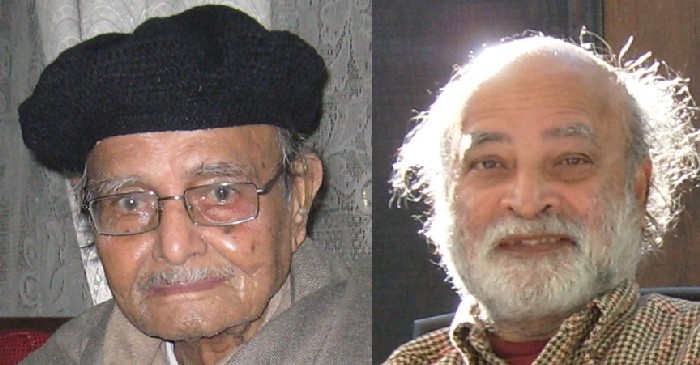

Growing up in the house where Sheelabhadra was just one of the many children, I still see him precisely as that - a loving, caring, responsive and responsible brother or, in my case, Dada. I dearly miss him. Oh, well. That’s life.

Kalyan Dutta-Choudhury

Berkeley

- Log in to post comments