Historical records provide ample evidence of the glorious textile traditions of Assam. At the request of the Koch king’s brother Prince Chilarai, Sri Sankaradeva took up the project of tapestry weaving for which he engaged the weavers of Tantikuchi or Barpeta. Eventually, the Brindabani Bastra was lost though the last place of resort for the Bastra was the Madhupur Sattra in Koch Behar.

Historical records provide ample evidence of the glorious textile traditions of Assam. At the request of the Koch king’s brother Prince Chilarai, Sri Sankaradeva took up the project of tapestry weaving for which he engaged the weavers of Tantikuchi or Barpeta. Eventually, the Brindabani Bastra was lost though the last place of resort for the Bastra was the Madhupur Sattra in Koch Behar.

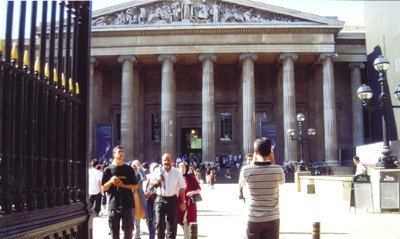

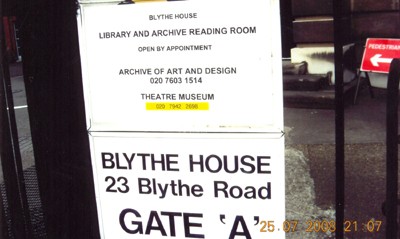

The Brindabani Bastra exemplars from Assam, woven from the 16th through the 18th century, measuring 120 cubits long and 60 cubits broad, are rare silk textile fragments depicting scenes from the life of Lord Krishna in a floral, naturalistic and preciously elegant style. They are preserved at the Blythe House, part of the British Museum. The Brindabani Batra has also been preserved in other museums such as Victoria & Albert Museum, Chepstow Museum in Wales, Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmedabad, Newark Museum in New Jersey, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Museum of Mankind in London, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Centro Internazionale delle Arti e del Costume in Venice and AEDTA Collection in Paris.

As Richard Blurton, the Curator at the British Museum explains, it was Perceval Landon, a British journalist and special correspondent for The Times who acquired the Brindabani Bastra on his expedition to Tibet in 1903 – 1904 in a town called Gobshi. And he gave the textile to British Museum in 1905 over a hundred years.

Rosemary Crill, a researcher and the author of the book Vrindavani Vastra: Figured Silks from Assam is a Senior Curator for Asian Development at the Victoria & Albert Musem. Her theory is that similar silk items emerged from Tibet to Assam for use during Vaishnavite rituals. It is not certain that the piece that is at British Museum belongs to the period of Sankaradeva. But pieces in other places are thought to be from about Sankardeva’s time.

Rosemary Crill, a researcher and the author of the book Vrindavani Vastra: Figured Silks from Assam is a Senior Curator for Asian Development at the Victoria & Albert Musem. Her theory is that similar silk items emerged from Tibet to Assam for use during Vaishnavite rituals. It is not certain that the piece that is at British Museum belongs to the period of Sankaradeva. But pieces in other places are thought to be from about Sankardeva’s time.

Museums would be very dull places if they could only display works that were made in their own countries or ethnic areas. What is most important is that art is displayed publicly and not hoarded in private collections. Galleries upon galleries of European and American museums can be seen filled by objects from ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome.

The colonial powers as we like to call them were the ones that preserved these treasures. Without them most of these artifacts would have disappeared by neglect. Many works of art have been preserved better as a result of being carefully handled in a foreign museum: there is the theory that the Elgin marbles would not have remained in their present condition in Athens because of the high air pollution levels, and similarly, many treasures would have been lost or destroyed forever had they not been removed by outsiders.

Perceval Landon must have understood the importance of Brindabani Bastra when he found it in Gobshi and decided to bring all the way from Tibet to a safer home like the British Museum.

Perceval Landon must have understood the importance of Brindabani Bastra when he found it in Gobshi and decided to bring all the way from Tibet to a safer home like the British Museum.

The world does seem a smaller place nowadays and to me these treasures do belong to the world. Cultural artifacts were local, then became national and are now global. Civilization is not a civilization if you do not share with others. The British Museum has done a good job of looking after them and identifying original locations and periods.

Coming from Assam, I can feel the sentiment of the Assamese people today being emotional about the Brindabani Bastra and making stubborn demands to bring back Brindabani Bastra to home.

In Assam, we cannot do anything to conserve what we already have. What about the wealth of historical treasures such as monuments and artifacts from our deep past? We talk about preserving and conserving the sattras in Majuli, but the State Archives, the State Museum, and the District libraries, to name a few are in dilapidated conditions. The Archaeological Survey of India has often complained that lack of adequate funds is largely responsible for its inability to protect the country’s museums and monuments.

The Assamese language has a very rich literary history; it is known to have written literature starting the thirteenth century, long before the printing press was brought to Assam by Europeans. The books were written painstakingly in hand on especially prepared paper from locally available resources. Some of these documents stored in the Assam State Museum and Gauhati University library in various conditions, most not so scientific. And as a result of the natural calamities, sheer neglect and lack of knowledge, the precious hand-written books, dating back centuries are slowly being destroyed.

Long years of neglect have taken their toll on a number of sites of historical importance in Assam; the ancient monuments of the state have failed to get the recognition that they deserve.

We demolish old temples. Not to speak of other sites, cracks on the famed Rang Ghar and Kareng Ghar, have now endangered the very existence of this structure. The Northbrook Gate in Jubilee Garden, Panbazar, at the very heart of Guwahati, is facing the brunt of neglect, and big cracks have appeared on the pillars. I remember as a child we used to play hide and seek inside the gate. This gate was constructed near Sukreswar Ghat on the bank of river Brahmaputra, where Northbrook alighted from the ship to visit the city in 1874. It also welcomed Lord Curzon during his visit to Guwahati from Kolkata.

Another sad example: we demolished our old Cotton College administrative building, which was built in 1901 initiated by Sir Henry Cotton. It was a part of our heritage. Wasn’t it?

The British have preserved English heritage in an admirable way. They aim to make people understand and appreciate the importance of an historic site to get the care and attention it deserves, from the first traces of civilization to the most significant buildings of the 20th century. They feel that it is their job to make sure that the historic environment of England is properly maintained and cared for. In Stratford -upon-Avon, Shakespeare’s cottage, the original structure of the building still stands as it did centuries ago. They renovate, redecorate but never change the structure.

Now both India and Assam want to claim back the Kohinoor Diamond and Brindabani Bastra. Good that the Taj Mahal was not mobile! It might have been on the other side of Big Ben today? This is sentiment!

Unfortunately this is like trying to rewind history. Where would you stop? Would every Roman artifact in Britain have to be sent to Italy, along with every Roman or Greek statue? Would the French want back statues that were cast from the bronze of their guns, could the South African’s claim back all their diamonds and gold? Should all Dutch paintings be sent back to Holland? It just wouldn’t work.

In Victoria & Albert Museum, one can see the famous Tipoo’s Tiger; it had been damaged in the Second World War. Also many works of Buddhist art from Central Asia was also damaged in Berlin and lost forever. In such a volatile world where are works of art safe?

Who can deny that Britain’s colonial misadventures of the past few centuries? But Britain has also brought a moral system, based on the rule of law, into the society.

We are no more than the summation of our experiences. Our experiences define our identity. In the case of the Brindabani Bastra, the problem is how can we establish the original ownership? So, far nothing has come up.

But again, when the State Government is not in a position to preserve and conserve the already existing artifacts, how can we be assured safe keep of the Brindabani Bastra in Assam?

But again, when the State Government is not in a position to preserve and conserve the already existing artifacts, how can we be assured safe keep of the Brindabani Bastra in Assam?

The climate of Assam is very humid. It rains torrentially during the monsoon season. The Brahmaputra and the many hundreds of big and small rivers and tributaries in Assam are prone to damaging floods almost every year. Earthquakes are fairly common as well. There are hardly any scientifically maintained archival sites.

However as a temporary measure, for the public viewing of the Brindabani Bastra, one can suggest a place like Srimanta Sankardev Kalashetra, Guwahati, provided it has scientific methods to preserve. The arrangement should be for a limited period only.

Once again, the Brindabani Bastra in its current location is much safer and available for many more people who might be interested in arts and culture.

As an Assamese, I feel fortunate that I am able to view this historic piece of textile in the British Museum where every care is taken to preserve and conserve.

Rini Kakati, London

- Log in to post comments

Comments

let those who want the

let those who want the brindabani bastra back first take of things that lie wasted in assam. there is no changing the fact that a large portion of the ambari excavation site in guwahati has for many years now been under the illegal occupation of the guwahati press club--of all organisations, one that is supposed to bring the sentinels of our society, our journalists, together. cotton college, the premier college of the state has had the privilege of burying under its indoor stadium, an ancient temple that could have been the pride of the institution. that itself should say something (if not everything) about how well we look after our heritage in assam. let the brindabani bastra be where it is--safe and sound. let the world admire what we have chosen, for some reason, to systematically destroy.

FULLY AGREED WITH YOUR VIEWS.

FULLY AGREED WITH YOUR VIEWS. WE SHOULD LEARN TO RESPECT WHAT WE HAVE IN HAND , FOR THE MOMENT. THE BASTRA WILL BE MORE APPROCHABLE IN BRITAIN TO THE RESEARCHERS.

CAN YOU PLEASE SEND ME A CLOSE UP PHOTO OF THE BASTRA ? WE NEED TO SHOW IT TO MORE PEOPLE.